Updated at 8:45 p.m. The Alexandria Police Department is investigating the posting of racist fliers in the Potomac Yard neighborhood of the city.

Four fliers were discovered posted in the 2100 block of Potomac Avenue on March 15, according to a resident who provided photos and information to ALXnow.

The resident notified the city of the “graffiti” via Alex311, and the fliers were subsequently removed from a light post and electrical box near Potomac Yard Park.

One of the fliers read in bold letters, “Strong families make strong nations,” a slogan used in fliers attributed to the white nationalist group Patriot Front.

Another flier is more explicit, reading: “Reclaim America: Patriot Front.”

ALXnow received word of more fliers and stickers posted around the area in February and March, and they were taken down by a longtime resident.

The group was formed after the 2017 “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville, according to the Southern Poverty Law Center, which found that more than 1,600 fliers attributed to the group have been found in Virginia alone.

APD said that no suspects have been identified, and posting hate speech and fliers is not a crime in Virginia.

According to the Anti-Defamation League:

- Patriot Front is a white supremacist group whose members maintain that their ancestors conquered America and bequeathed it to them, and no one else.

- Patriot Front justifies its ideology of hate and intolerance under the guise of preserving the ethnic and cultural origins of its members’ European ancestors.

- Patriot Front spreads its hateful propaganda via the internet and by distributing banners, fliers, posters, and stickers.

- Since 2019, Patriot Front has been responsible for the vast majority of white supremacist propaganda distributed in the United States.

- One of the United States’ most visible white supremacist groups, Patriot Front participates in localized “flash demonstrations” across the nation.

- While claiming loyalty to America as a nation, Patriot Front seeks to form a new state, one that advocates for the “descendants of its creators,” namely white men.

Alexandria’s Old Town and Del Ray neighborhoods were last peppered with racist fliers in 2017.

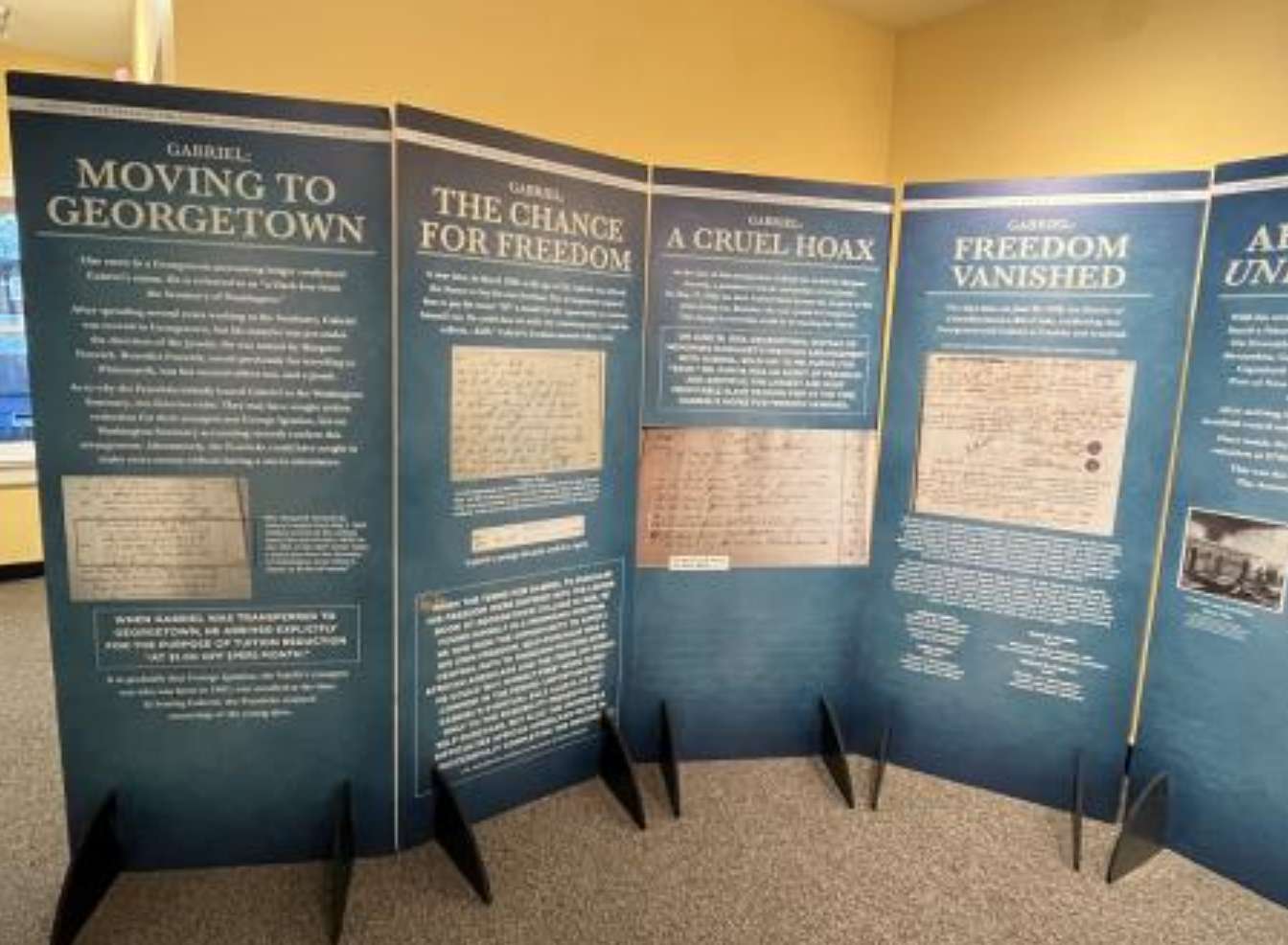

A new temporary exhibit at Freedom House Museum until April documents the life of a teenager enslaved at Washington Seminary in D.C.

“Searching for Truth in the Garden” reveals a story of Gabriel, a 13-year-old boy who was enslaved at the school — later renamed Gonzaga College High School — in 1829.

The research was conducted by seven Gonzaga students and Georgetown University history professor Adam Rothman, who started the project in 2016. Rothman was speaking to students about his work with Georgetown’s Working Group on slavery when a student asked about connections between the school and slavery. Rothman invited students to research the question at Georgetown, which they did in the summers of 2017 and 2018.

“Their work shows how students can be inspired to go beyond textbooks to take a deeper dive into our history and bring to light the untold stories of the American historical narrative,” said Audrey Davis, director of the city’s African American History Division. “With Gabriel, we learn about the horrors of the domestic slave trade, and tragic life of one enslaved 13-year-old boy.”

According to the city, the group studied accounting books, written histories, enrollment records, and other original documents related to the schools, including the sale of 272 slaves by the Jesuits in 1838.

The project also inspired an ancestry project with Georgetown University.

“According to In 1838, Maryland’s Jesuit priests sold hundreds of men, women, and children to Southern plantations to raise money for the construction of Georgetown University,” Georgetown University said. ” Though they faced incredible hardship, most didn’t perish. They married and raised children. Today, more than 8,000 of their descendants have been located through genealogical research. Use this site to search for an ancestor and to hear the stories of the descendants.”

Gonzaga history teacher Ed Donnellan helped in the project.

“This exploration of what is a very painful past for Gonzaga and for the Society of Jesus is very important,” Donnellan said. “It’s my hope and prayer that this begins something in our community that helps us heal, helps us move forward, and helps us be honest about where we’ve come from and who we are today.”

Alexandria has identified dozens of racially restrictive zoning covenants, many of which have been on the books for more than 100 years.

Next Tuesday, City Council will review a report on racially restrictive covenants that, during much of the 20th century, prohibited non-white residents from moving into subdivisions and neighborhoods throughout the city. City staff are also asking Council to review a process for a property owner to get the illegal covenant by filing for a certificate of release from the Alexandria Circuit Court.

The research was part of the city’s Zoning for Housing/Housing for All initiative, which ultimately resulted in a citywide zoning overhaul approved by City Council last month.

City staff said in a memo that they were aware of only three subdivisions that racially segregated residents:

- the W.I. Angels West End subdivision, which includes Angel Park

- the Abington subdivision, which includes city land on Randolph Avenue

- and the Eagle Crest Subdivision, which includes a portion of Fort Ward Park

“Soon after we became aware of these properties, we went through the Circuit Court’s process for removing the covenants from the City owned portions of these subdivisions,” city staff said. “This process was completed for these three properties in November and the certificates of release have all been recorded.”

Krystn Moon of the University of Mary Washington, who the city hired to gather information on the history of the covenants, found dozens more properties, in Alexandria as well as Arlington and Fairfax counties. This includes 33 properties owned by the city — for fire stations, parks or the public right-of-way — and city entities, such as the Alexandria Redevelopment Housing Authority or Alexandria City Public Schools.

At least 20 city properties in the Del Ray, Rosemont and St. Elmo’s subdivisions will require additional research.

According to Moon’s report, the covenants were commonly used in the 20th century by local governments, developers, and property owners to maximize real estate values with racially restrictive language. They are now illegal in Virginia and unenforceable after the passage of the Fair Housing Act in 1968.

“(C)lass politics informed the inclusion of certain types of restrictions and ordinances, which overlapped with racial attitudes among many white residents,” Moon wrote.

“Instead of ensuring housing accessibility for all residents, they became one of the many tools in the racial segregationist toolbox to control where African Americans and other minorities might live,” she continued. “As such, they privileged the production of wealth for white, middle- and upper-class homeowners by prioritizing single-family dwellings and their property values over all other types of development.”

City Council Member Alyia Gaskins directed the City Attorney’s Office to research and detail a process for removing these covenants from city properties.

“Removing these covenants is one way to further demonstrate our commitment to building a more equitable city,” Gaskins said. “Furthermore, the City has an opportunity to be a model for homeowners who might not know that there is a restriction on their property and/or how to remove it.”

Covenants commonly made the property exclusive to the “Caucasian Race” to exclude not just African Americans but also Jews, Native Americans, Seventh Day Adventists and persons of Armenian, Chinese, Japanese, Mexican, Persian and Syrian ancestries, she said.

A Rosemont deed, for instance, says that “no part of the said premises nor any interest therein, shall be sold, leased, rented, or in any way conveyed to anyone not of the Caucasian race,” while a George Washington Park deed singled out the property could not be sold or conveyed to anyone of “African descent.”

According to the report:

In 1912, Rosemont became the first subdivision in Alexandria to include racial restrictions on specific lots. A year later, an unnamed development on Oronoco, Fayette, Princess, and Payne Streets in the Uptown neighborhood included similar language in its deeds. George Washington Park, which Alexandria annexed from Fairfax County in 1915, had restrictions as early as 1909.

By the 1920s, new subdivisions that were either part of or adjacent to George Washington Park and Rosemont inserted restrictive language into their deeds. Mount Vernon Park, Temple Park, Glendale, Brenton, and the Adams Estate (a development west of Rosemont along King Street) either limited renting and owning to the “Caucasian Race” or excluded African Americans.

In Alexandria, African Americans faced systematic discrimination throughout this period and were increasingly subjected to restrictive covenants that impacted where they could live, work, and own property. Other restrictive covenants, such as the one for Rosemont, stated that only Caucasians were permitted to own or inhabit a particular property. Interestingly, the deed from Uptown even barred corporate ownership. The inclusion of this language was most likely a reference to Peoples Pleasure Park Co. v. Rohleder (1908), in which the Virginia State Supreme Court Case ruled a corporation “is not a person” and “had no ‘color’ or race.” This decision allowed African American-owned corporations to buy properties with race-based restrictions unless they were specifically barred. Finally, the restrictions in Rosemont included a sunset clause, allowing them to end on January 1, 1928. The restrictions at George Washington Park and the unnamed development in Uptown excluded African Americans in perpetuity.

Moon found that real estate lawyer and Congressman Howard W. Smith (in office from 1930 to 1966) was an ardent segregationist, and inserted restrictive covenants into deeds targeting “all non-white owners and/or occupants,” and that on said property “any building that may be erected thereon shall never be sold, rented, or let to any person not of the Caucasian Race.”

The following is the list of city-owned properties that have a racially restrictive covenant:

Westover Subdivision (Alexandria Deed 152-272)

- 900 Second Street (Fire Station)

- 1028 Powhatan St (Fire Station’s Parking)

- 1024 Powhatan St (Fire Station’s Parking)

- 1010 Douglas St (Powhatan Park)

- 1009 Douglas St (Powhatan Park)

Monticello Park (Arlington County Deed 261-50)

- 2908 A Richmond LA (Monticello Park)

- 2801 Cameron Mills Rd (Fire Station)

- 2601 Cameron Mills Rd (George Mason Elementary School)

Threadgill (Alexandria Deed 121-299)

- 1607 Suter St (Metro Linear Park)

- 1614 Suter St (Metro Linear Park)

- 1625 Princess St [possibly 1629 Princess too, which is the right of way along the railroad tracks] (Metro Linear Park)

Baggett Tract (Alexandria Deed 167-350)

- 340 Buchanan St (Metro Linear Park)

- 300 Buchanan St (Metro Linear Park)

Fagelson’s Addition to Dempsey (Arlington County Deed 201-269)

- 810 Chetworth Pl (Chetworth Park)

Rosemont (Properties Restricted on Specific Deeds)

- 4 Sunset Dr (Alexandria Deed 65-449) (Sunset Mini Park)

- 201 Rucker Place (Alexandria Deed 106-105) (Beach Park)

- 701 Johnston Pl (Alexandria Deed 106-105) (Maury School Land)

Wapleton (Fairfax County Deed G-15-45)

- 530 Cameron Station Bv (Armistead L. Boothe Park)

- 270 S Reynolds St (Park-Open Space)

- Beverley Plaza (Properties Restricted on Specific Deeds)

- 3909 Bruce St (Four Mile Run Park) (Alexandria Deed 156-290 and 157-333)

Cameron Park (Properties Restricted on Specific Deeds)

- 20 Roth St (Park-Witter Fields N of Business Center Dr) (Fairfax Deed 192-193)

- 3224 Colvin St (Parking Lot) (Fairfax Deed U-9-128)

Waverly Taylor (Alexandria Deed 193-182)

- 3000 Fulton St (Island between Roads)

Oakcrest (Alexandria Deed 162-278)

- 1521 Dogwood Dr (Sheltered Homes of Alexandria)

Beverley Park (Properties Restricted on Specific Deeds)

- 610 Notabene Dr (Hawaiian Garden Apartments) (Alexandria Deed 181-436)

- 3910 Old Dominion Bv (Glebe Park Apartments) (Alexandria Deed 181-436)

- 3902 Old Dominion Bv (Glebe Park Apartments) (Alexandria Deed 181-436)

- 3961 Old Dominion Bv (Old Dominion Housing Limited Partnership) (Alexandria Deed 176-455)

Veach Tract (Properties Restricted on Specific Deeds)

- 27 S Bragg St (15 Townhomes) (Fairfax Deed 449-127 and Fairfax Deed 421-42)

Fort Ward Heights (Fairfax County Deed Q-13-400)

- 4560 Strutfield Ln (Palazzo at Park Center)

Brenton (Properties Restricted on Specific Deeds)

- 5 W Braddock Rd (Park) (Arlington County Deed 233-229)

- 1005 Mt Vernon Av (George Washington Junior High School) (Arlington County Deed 255-588 and Alexandria Deed 90-90)

Dunton Property (Fairfax County Deed W-14-171)

- 5325 Polk Av (Polk Park)

While the city is making strides to honor the victims of two Alexandria lynchings, a member of the Alexandria Community Remembrance Project noted in a recent meeting that a third victim — the first recorded in the city — has been neglected in part due to a technicality.

Thanks in large part to the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI), a non-profit based out of Alabama working to commemorate victims of lynching, the city has started to do more work to commemorate the victims of lynchings in 1897 and 1899. In particular, however, the EJI focuses on lynchings between 1877 and 1950, while Alexandria’s first recorded lynching occurred over ten years before that period started.

“I think we should have a historic OHA marker for John Anderson, who was killed by a mob of white men on Christmas Day in 1865 at West and King Street,” said Tiffany Pache of the Alexandria Community Remembrance Project. “I think we should start talking about him as our first documented lynching.”

One of the goals of the Alexandria Community Remembrance Project was to dig through archives and see if other lynchings in the city’s history might not have been as noted as the deaths of Joseph McCoy in 1897 and Benjamin Thomas in 1899. A newsletter from the project in December 2021 compiled accounts from various news organizations about the murder of John Anderson on Christmas Day in 1865.

A group of white men, just after the end of the Civil War, undertook a campaign of violence across the city, attacking several Black residents and causing serious injuries. John Anderson, a Black man who resided near King Street, left his Christmas dinner to try and put an end to the violence after he heard a Black soldier had been beaten. However, after approaching the mob, Anderson was beaten and fatally shot.

According to the project’s newsletter:

Anderson crossed the street diagonally toward John Mankin, who stood on Gregg’s corner in a dark coat and slouch hat. Anderson did not speak again. As he stepped over the curbstone, Mankin attempted to strike him, but Anderson deftly blocked the punch. As Anderson readied for a fist fight, Mankin beckoned a crowd of whites. He pulled something out of his pocket. Extending his arm, he revealed a gun and shot Anderson in the thigh.

Anderson turned. Suddenly, John’s brother Oscar Mankin was there, at the forefront of a gang of white men. He shot Anderson in the head. Anderson took a few steps and fell to the ground, where he was pelted with stones and bricks thrown by the mob. Huntington and John L. Heck were there, as was George Javins, according to witnesses. John Anderson died five days later from a gunshot wound to the left side of his skull.

Pache said while the murder is outside of the dates covered by the EJI, it still merits some recognition from the city.

While the newsletter extensively covers the story of the murder and the aftermath, Pache said there are also likely court records from the incident that the city hasn’t accessed.

“The current research is based on newspaper accounts, but there was also a court case that tried the men,” Pache said. “[They] were convicted and sent to Ohio, then they were released after only a few months. There was a court-martial, because the military was still here, so I want to get my hands on that.”

A remembrance ceremony is planned next week to mark the 124th anniversary of the lynching of Alexandria teen Benjamin Thomas and the unveiling of a new historic marker.

Thomas, one of two black Alexandrians murdered by lynch mobs, was 16 when he was hanged and shot at the corner of King and Fairfax streets in 1899.

According to the City of Alexandria:

Thomas was arrested on Monday, August 7, 1899, for allegedly assaulting a white girl, but this was never proven. That night, Black community leaders warned police and the mayor that another lynching might occur, similar to the lynching of Joseph McCoy two years earlier on April 23, 1897. When the authorities refused their entreaties, the African American Alexandrians tried to protect Thomas themselves, standing guard near where he was being held. The police arrested them, and the next morning, they were, tried, fined and sent to the chain gang. The next night, somewhere between 500 and 2000 Alexandrians took Benjamin Thomas from the city jail on St. Asaph Street, dragged him over cobblestones for half-a-mile to the corner of King and Fairfax Streets where they hanged and shot the young man.

The ceremony will take place at 6 p.m. at 401 N. St. Asaph Street.

“Participants will be invited to solemnly walk the half-mile trail the lynch mob took down St. Asaph Street to King Street and then to the intersection with Fairfax Street,” the city’s website said. “Upon arriving at the site of the lynching of Benjamin Thomas we will hold a wreath-laying ceremony.”

City Hall, the lamp post where Thomas was lynched, and the George Washington Masonic Memorial will be lit up in purple to commemorate Thomas.

Image via City of Alexandria

Despite previous commitments to diversity, including recruitment efforts and leadership from a Black chief of police, the Alexandria Police Department is contending with diversity issues.

Officers tell ALXnow a reorganization that occurred after Chief Don Hayes stepped into his leadership role in 2021 rewarded close connections and disregarded officers of color and civilian staff, which they say is a sign that Hayes does not want to make waves.

Now, most of APD’s leadership remains white and officers of color say they are being passed over.

“The way it’s set up now, the department’s leadership will be completely white for 20 years,” said an APD employee who spoke anonymously. “[The chief’s] actions always seem to have an adverse effect on employees of color.”

The department’s leadership of sergeant through captain is mostly white, with people of color making up a relatively small percentage. APD has no non-white captains or detectives, and only 10 sergeants of color out of 38 sergeant positions, according to a staffing directory provided by APD.

The two highest-ranking Black women in the department are sergeants, per the directory. There are no Asian officers above the rank of sergeant, and there is only one Hispanic lieutenant.

Some officers have tried many avenues for addressing this, including ethics complaints, meetings with Hayes and possibly unionizing, but have not gotten anywhere, fearing retaliation.

“I have thought about leaving,” a APD employee said. “Why should I go for a promotion? I want to get my money and I just want to go home and be left alone when I’m off the clock.”

ALXnow interviewed nine employees who spoke under the condition of anonymity out of fear of retaliation. Those employees alleged that recent departmental actions aren’t simply an oversight, but instead a concentrated effort against minorities. Hayes declined to be interviewed on diversity and his restructuring over the course of the last two months by ALXnow.

“There are great people, employees, officers and civilian staff that work at APD,” an employee said. “But there are also some very rotten ones. And unfortunately, some of those rotten ones work in the middle management and leadership. And they have an impact on the morale and the culture of the organization.”

“Unfortunately, unless someone ever notices it, it’s just gonna be a slippery slope,” the employee continued. “If they’re all there, the turnover is going to be high.”

Staff also feel like Hayes could have been a mentor, but is alienating them and not often present due to his other duties as a pastor. Since last summer, Hayes has been interim pastor at Mount Zion Baptist Church in Arlington.

The fallout from a lack of diversity in middle management is something that people who specialize in diversity initiatives say is a key hindrance to changing the status quo.

At a City Council meeting last night (Tuesday), Alexandria Mayor Justin Wilson unveiled the next stage of plans to ramp up the renaming of streets that honor Confederate leaders, the Washington Post first reported.

While the city has renamed the Alexandria portion of Jefferson Davis Highway and removed the Appomattox statue, streets honoring Confederate leaders like the “Gray Ghost” John Singleton Mosby or Ku Klux Klan founder Nathan Bedford Forrest still exist around the city.

Discussions to rename more streets began last October, but there’s a much longer history of Civil War names on streets dividing Alexandria. As of 2018, about 60 streets potentially were named for Confederate leaders, but in some cases — such as Lee Street — the historical record is unclear about a street’s namesake.

The mayor said his new plans stem from the conversation that kicked off last fall.

“Last year, I talked on the dais about a process and a deliberate schedule to identify street names in our city that really were designed as a permanent protest against the civil rights movement and growing political power for African Americans in our city,” Wilson said. “Those places and those honors have no place in our city.”

Wilson said his plan is for two committees to work in tandem to find both streets to rename and suitable names to replace them.

Historic Alexandria Resources Commission would develop a list of people, events and locations that deserve honors, with a focus on women and minorities — people traditionally underrepresented in city honors. The City Council Naming Committee, meanwhile, would identify which streets should be prioritized for renaming.

Wilson said the city should aim to rename three streets each year, which would “keep us busy for quite a while” but would also give city leadership space to determine if that’s too ambitious or not ambitious enough.

The proposal found widespread support on the City Council, where others said they had first-hand experience with how difficult the legacy of Confederate honors can be to escape.

“As someone who bought a home in Alexandria just a few years ago on the West End, it was very startling how many houses we looked at were on streets with names I would have a hard time living on,” said City Council member Kirk McPike. “We thought we dodged that, but as it turns out our current street is named after a Confederate naval vessel.”

The memo is set for review as part of the city’s budget process. City Manager James Parajon is scheduled to present a draft of the budget to the City Council on Feb. 28, followed by a period of meetings and discussions that culminate with a vote on the budget in May.

At tonight’s Alexandria City Council meeting, @justindotnet proposed a plan to speed up the renaming of the 41+ streets in town named after Confederate leaders.

It would direct a cmte. to rename 3 of those a year, drawing from a list of new honorees emphasizing women & POC pic.twitter.com/nLZ1w6p7qI

— Teo Armus (@teoarmus) January 11, 2023

Years before Alexandria would grapple with collective bargaining and the legacy of discrimination in schools, Virginia was ruled by a political faction dead-set on fighting unionization and integration.

Alexandria reporter Michael Lee Pope — a reporter with the Alexandria Gazette who has frequently covered Virginia’s state politics for WAMU — announced a new book last week that dives into the history of The Byrd Machine, a political operation led by Harry Byrd that dominated Virginia politics during the mid-20th century.

The Byrd Machine in Virginia charts the rise and fall of the eponymous political block, with both a look back at the history of the previous “machines” that made The Byrd Machine possible.

Pope said Byrd’s career started as a movement aimed primarily at eliminating debt.

“He got into this political debate when he was in the Senate about road building and not making debt. This is his whole thing, he’s very consistent, he doesn’t like debt.”

Pope said Byrd’s early campaign was about paying for projects as you go and he developed a name for himself as someone making the state government pay its debt. Byrd had a reputation as a penny pincher, going back to driving to Maryland every day to get cheaper rolls of paper for a failing Winchester newspaper he owned.

After being elected as governor in 1926, Byrd started to take measures to coalesce power and keep those in the Byrd Machine in power.

Two of the biggest legacies of Byrd, Pope said, is his opposition to unions and integration. In 1946, workers at VEPCO, the predecessor to Dominion Energy, attempted to form a strike and unionize. Governor William Tuck, a successor to Byrd and a part of his machine, drafted the workers into the state’s national guard and threatened to court martial them if they attempted to strike.

“So many people blame the Byrd machine for all manner of things,” Pope said. “This issue of collective bargaining… only recently given the legal ability to do collective bargaining. That was taken away in the 90s. It would be easy to blame Byrd and say ‘that’s the Byrd machine’ but that’s 1990s era politics.”

Still, Pope said the anti-unionization work in the 90s was still part of the legacy of Byrd’s politics.

“At the same time, don’t forget these people pioneered union-busting in a way that was visionary for its time,” Pope said, “There is an important part of collective bargaining as part of that legacy.”

The more well-known parts of Byrd’s legacy is arguably the machine’s opposition to integration. It was also the position that set the stage for the machine’s downfall. The Byrd Machine was instrumental in keeping schools segregated to the point of closing public schools rather than seeing them integrated in the late 1950s.

Though the machine had a “swan song” in the 1960s, Pope said the controversies around massive resistance ultimately led to the fracturing of The Byrd Machine as the Lyndon Johnson presidency divided the loyalties of racist southern Democrats.

Pope said he is planning to host a launch event for the book at The Athenaeum (201 Prince Street) on Thursday, Oct. 20, at 7 p.m.

The Alexandria Community Remembrance Project (ACRP) has organized a pilgrimage to the Equal Justice Initiative’s National Memorial for Peace and Justice and Legacy Museum next month, and today (Tuesday) is the last chance for locals to register to join the trip.

Community members will transport soil from where two Black Alexandrians were lynched. The trip will involve visits to historical sites around Alabama and evening programs with guest speakers.

“You can choose to travel with us by bus from Alexandria, or you can join us in Montgomery,” the city website said. “This trip, October 6-10, includes chartered busses, discounted hotel stays, curated social justice tours, most meals and two evening programs with guest speakers.”

Joining the trip will also enroll members in the Alexandria Community Remembrance Project.

“We hope that you will join us in the future, as we continue to meet, educate, reflect and build a more inclusive and equitable Alexandria,” the website said.

Trips with independent travel are $485 or $585 to join on the chartered bus. Those interested in supporting the trip can donate online.

A new grant-funded program is coming to Alexandria this fall to help parents talk to children about issues around race and privilege.

The program, called Conversations About Race & Belonging, is run through a local organization called Open Horizon and is launching in Alexandria this fall.

“This program invites parents of K-12 students in Alexandria’s public and independent schools to learn skills to engage in meaningful conversations that often feel challenging, awkward and uncomfortable, using race, identity, and privilege as a focusing lens,” the release said. “We also are promoting this program to parents who are professional librarians, counselors, coaches, and building staff within those Alexandria systems that serve children, regardless of where their children go to school.”

The release said part of the goal is to engage networks, like neighbors or members of social groups, and the city is encouraging those groups to attend together to support one another.

The program page said a nominal fee of $25 is asked but not required. The next round of applications is scheduled to close on July 31.

“We are registering participants, but are limited to 30 seats, so we invite you to please share this opportunity with any Alexandria parents who might be interested, either for themselves or for other parents in their social, school, neighborhood or faith groups,” the release said. Details about the program, as well as the registration link, can be found online at this Parents Program info sheet.”